|

HABITAT

| ECONOMY

| CLASSIFICATION

| SOCIETY

& KINSHIP | MARRIAGE

RELIGION

| CRISIS

RITES | RITUALS

| BELIEF

IN THE SUPERNATURAL NORMS

& CUSTOMS

In India there is an amalgam of 437 tribes, and in Orissa the number is

sixty two. According to 1991 Census, in Orissa the total strength of tribal

population is approximately seven million which constitutes 22.21% of the

total population of the State.

Linguistically the tribes of India are broadly classified into four

categories, namely (1) Indo-Aryan speakers, (2) Dravidian speakers, (3)

Tibeto-Burmese speakers, and (4) Austric speakers. ln Orissa the speakers of

the Tibeto-Burmese language family are absent, and therefore Orissan tribes

belong to other three language families. The Indo-Aryan language family in

Orissa includes Dhelki-Oriya, Matia, Haleba, Jharia, Saunti, Laria and Oriya

(spoken by Bathudi and the acculturated sections of Bhuyans, Juang, Kondh,

Savara, Raj Gond etc.). The Austric language family includes eighteen tribal

languages namely, Birija, Parenga, Kisan, Bhumiji, Koda, Mahili Bhumiji,

Mirdha-Kharia, Ollar Gadaba, Juang, Bondo, Didayee, Karmali, Kharia, Munda,

Ho, Mundari and Savara. And within the Dravidian language family there are

nine languages in Orissa, namely, Pengo, Gondi, Kisan, Konda, Koya. Parji,

Kui, Kuvi and Kurukh or Oraon.

The tribes of Orissa though belong to three linguistic divisions, yet they

have lots of socio-cultural similarities between them. These commonalities

signify homogeneity of their cultures and together they characterise the

notion or concept of tribalism. Tribal societies share certain common

characteristics and by these they are distinguished from complex or advanced

societies. In India tribal societies had apparently been outside the main

historical current of the development of Indian civilization for centuries.

Hence tribal societies manifest such cultural features which signify a

primitive level in socio-cultural parameter.

Habitat: A major portion of the tribal

habitat is hilly and forested. Tribal villages are generally found in areas

away from the alluvial plains close to rivers. Most villages are uniethnic in

composition, and smaller in size. Villages are often riot planned at all.

Economy: Tribal economy is characterised

as subsistence oriented. The subsistence economy is based mainly on

collecting, hunting and fishing (e.g., the Birhor, Hill Kharia), or a

combination of hunting and collecting with shifting cultivation (e.g., the

Juang,, Hill Bhuyan, Lanjia Saora, Kondh etc.) Even the so-called plough

using agricultural tribes do often, wherever scope is available, supplement

their economy with hunting and collecting. Subsistence economy is

characterised by simple technology, simple division of labour, small-scale

units of production and no investment of capital. The social unit of

production, distribution and consumption is limited to the family and

lineage. Subsistence economy is imposed by circumstances which are beyond the

control of human beings, poverty of the physical environment, ignorance

of efficient technique of exploiting natural resources and lack of capital

for investment. It also implies existence of barter and lack of trade.

Considering the general features of their (i)

eco-system, (ii) traditional economy, (iii) supernatural beliefs and

practices, and (iv) recent "impacts of modernization", the tribes

of Orissa can be classified into six types, such as: (1)

Hunting, collecting and gathering type, (2) Cattle-herder type, (3) Simple

artisan type, (4) Hill and shifting cultivation type, (5) Settled agriculture

type and (6) Industrial urban worker type.

Each type has a distinct style of life which could be best understood in the

paradigm of nature, man and spirit complex, that is, on the basis of

relationship with nature, fellow men and the supernatural.

(1) Tribes of the first type, namely Kharia, Mankidi,

Mankidia and Birhor, live in the forests of Mayurbhanj, Keonjhar and

Sundargarh districts, exclusively depend on forest resources for their

livelihood by practising hunting, gathering and collecting. They live in tiny

temporary huts made out of the materials found in the forest. Under

constraints of their economic pursuit they live in isolated small bands or

groups. With their primitive technology, limited skill and unflinching

traditional and ritual practices, their entire style of life revolves round

forest. Their world view is fully in consonance with the forest eco-system.

The population of such tribes in Orissa though is small, yet their impact on

the ever-depleting forest resources is very significant. Socio-politically

they have remained inarticulate and therefore have remained in a relatively

more primitive stage, and neglected too.

(2) The Koya which belongs to the Dravidian linguistic

group, is the lone pastoral and cattle-breeder tribal community in Orissa.

This tribe which inhabits the Malkangiri District has been facing crisis for

lack of pasture.

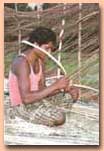

(3) In Orissa Mahali and Kol-Lohara practise crafts

like basketry and black-smithy respectively. The Loharas with their

traditional skill and primitive tools manufacture iron and wooden tools for

other neighbouring tribes and thereby eke out their existence. Similarly the

Mahalis earn their living by making baskets for other communities. Both the

tribes are now confronted with the problem of scarcity of raw

materials. And further they are not able to compete with others, especially

in the tribal markets where goods of other communities come for sale, because

of their primitive technology. (3) In Orissa Mahali and Kol-Lohara practise crafts

like basketry and black-smithy respectively. The Loharas with their

traditional skill and primitive tools manufacture iron and wooden tools for

other neighbouring tribes and thereby eke out their existence. Similarly the

Mahalis earn their living by making baskets for other communities. Both the

tribes are now confronted with the problem of scarcity of raw

materials. And further they are not able to compete with others, especially

in the tribal markets where goods of other communities come for sale, because

of their primitive technology.

(4) The tribes that practise hill and shifting

cultivation are many. In northern Orissa the Juang and Bhuyan, and in

southern Orissa the Kondh, Saora, Koya, Parenga, Didayi, Dharua and Bondo

practise shifting cultivation. They supplement their economy by foodgathering

and hunting as production in shifting cultivation is low. Shifting

cultivation is essentially a regulated sequence of procedure designed to open

up and bring under cultivation patches of forest lands, usually on hill

slopes. (4) The tribes that practise hill and shifting

cultivation are many. In northern Orissa the Juang and Bhuyan, and in

southern Orissa the Kondh, Saora, Koya, Parenga, Didayi, Dharua and Bondo

practise shifting cultivation. They supplement their economy by foodgathering

and hunting as production in shifting cultivation is low. Shifting

cultivation is essentially a regulated sequence of procedure designed to open

up and bring under cultivation patches of forest lands, usually on hill

slopes.

In shifting cultivation the practitioners follow a pattern of cycle of activities

which are as follows: (i) Selection of a patch of hill slope or forest land

and distribution or allotment of the same to intended practitioners (ii)

Worshipping of concerned deities and making of sacrifices, (iii) Cutting of

trees, bushes, ferns etc., existing on the land before summer months, (iv)

Pilling up of logs, bushes and ferns on the land, (v) Burning of the withered

logs, ferns and shrubs etc. to ashes on a suitable day, (vi) Cleaning of the

patch of land before the on-set of monsoon and spreading of the ashes evenly

on the land after a shower or two, (vii) Hoeing and showing of seeds with

regular commencement of monsoon rains, (viii) Crude bunding and weeding

activities follow after sprouting of seeds, (ix) Watching and protecting the

crops, (x) Harvesting and collecting crops, (xi) Threshing and storing of

corns, grains etc., and (xii) Merry-making. In these operations all the

members of the family are involved in some way or the other. Work is

distributed among the family members according to the ability of individual

members. However, the head of the family assumes all the responsibilities in

the practice and operation of shifting cultivation. The adult males, between

18 and 60 years of age under-take the strenuous work of cutting tree, ploughing

and hoeing, and watching of the crops at night where as cutting the bushes

and shrubs, cleaning of seeds for sowing and weeding are done by women.

Shifting cultivation is not only an

economic pursuit of some tribal communities, but it accounts for their total

way of life. Their social structure, economy, political organization and

religion are all accountable to the practice of shifting cultivation. Shifting cultivation is not only an

economic pursuit of some tribal communities, but it accounts for their total

way of life. Their social structure, economy, political organization and

religion are all accountable to the practice of shifting cultivation.

In the past, land in the tribal areas had not been surveyed and settled.

Therefore, the tribals freely practised shifting cultivation in their

respective habitats assuming that land, forest, water and other natural

resources belonged to them. The pernicious, yet unavoidable practise of

shifting cultivation continues unchecked and all attempts made to wean away

the tribals from shifting cultivation have so far failed. The colonization

scheme of the State Government has failed in spirit.

In certain hilly areas terraces are constructed along the slopes. It is

believed to be a step towards settled agriculture. Terrace cultivation is

practised by the Saora, Kondh and Gadaba. The terraces are built on the

slopes of hill with water streams.

(5) Several large tribes, such as, Santal, Munda, Ho,

Bhumij, Oraon, Gond, Mirdha, Savara etc. are settled agriculturists, though

they supplement their economy with hunting, gathering and collecting. Tribal

agriculture in Orissa is characterised by unproductive and uneconomic

holdings, land alienation indebtedness, lack of irrigation facilities in the

undulating terrains, lack of easy or soft credit facilities as well as use of

traditional skill and primitive implements. In general, they raise only one

crop during the monsoon, and therefore have to supplement their economy by

other types of subsidiary economic activities.

Tribal communities practising settled agriculture also suffer from further

problems, viz: (i) want of record of right for land under occupation, (ii)

land alienation (iii) problems of indebtedness, (iv) lack of power for

irrigation (v) absence of adequate roads and transport, (vi) seasonal

migration to other places for wage-earning and (vii) lack of education and

adequate scope for modernization.

(6) Sizable agglomeration of tribal population in Orissa has

moved to mining, industrial and urban areas for earning a secured living

through wage-labour. During the past three decades the process of industrial

urbanization in the tribal belt of Orissa has been accelerated through the

operation of mines and establishment of industries. Mostly persons from

advanced tribal communities, such as Santal, Munda, Ho, Oraon, Kisan,

Gond etc. have taken to this economic pursuit in order to relieve pressure

from their limited land and other resources.

In some instances industrialization and mining operations have led to uprooting

of tribal villages, and the displaced became industrial nomads. They lost

their traditional occupation, agricultural land, houses and other immovable

assets. They became unemployed and faced unfair competition with others in

the labour market, Their aspiration - gradually escalated, although they

invariably failed to achieve what they aspired for. Thus the net result was

frustration.

The overall kinship system

of the tribes may be label led as tempered classificatory. In terminology the

emphasis lies on the unilinear principle, generation and age. Descent and

inheritance are patrilineal and authority is patripotestal among all the

tribal communities of Orissa.

Among the tribes there is very little specialization of social roles, with

the exception of role differentiation in terms of kinship and sex and some

specialization in crafts, the only other role specializations are Head-man,

Priest, Shaman and the Haruspex.

There is very little rigid stratification in society. The tendency towards

stratification is gaining momentum among several settled agricultural tribes

under the impact of modernisation. The tribes of Orissa are at different

levels of socio-economic development.

The position of priest, village headman and the inter-village head-man are

hereditary. The village headman is invariably from original settlers' clan of

the village, which is obviously dominant. Punishments or corrective measures

are proportional to the gravity of the breach of set norms or crime, and the

punishments range from simple oral admonition to other measures, such as

corporal punishments, imposition of fines, payment of compensation,

observance of prophylactic rites and excommunication from the community.

Truth of an incident is determined by oath, ordeals and occult mechanism.

As regards the acquisition of brides for marriage,

the most widely prevalent practice among the tribes of Orissa is through

"capture", although other practices, such as, elopement, purchase,

service and negotiation are also there. With the passage of time negotiated

type of marriage, which is considered prestigious, is being preferred more

and more. Payment of bride-price is an inseparable part of tribal marriage,

but this has changed to the system of dowry among the educated sections.

The religion of the Orissan tribes is

an admixture of animism, animalism, nature-worship, fetishism, shamanism,

anthropomorphism and ancestor worship. Religious beliefs and practices aim at

ensuring personal security and happiness as well as community well-being and

group solidarity. Their religious performances include life-crisis rites,

cyclic community rites, ancestor and totemic rites and observance of taboos.

Besides these, the tribals also resort to various types of occult practices.

In order to tide over either a personal or a group crisis the tribals begin

with occult practices, and if it does not yield any result the next recourse

is supplication of the supernatural force.

Crisis Rites: As most of the

tribes of Orissa, practise agriculture in some form or the other, and as rest

others have a vital stake in agriculture, sowing, planting, first-fruit

eating and harvest rites are common amongst them. Their common cyclic rites

revolve round the pragmatic problems of ensuring a stable economic condition,

recuperation of the declining fertility of soil, protection of crops from

damage, human and live-stock welfare, safety against predatory animals and

venomous reptiles and to insure a good yield of annual and perennial crops.

The annual cycle of rituals commence

right from the initiation of agricultural operation, for instance, among the

Juang, Bhuyan, Kondh, Saora, Gadaba, Jharia, Didayee, Koya and Bondo, who

practise shifting cultivation. The annual cycle begins with the first

clearing of hill slopes during the Hindu month of Chaitra (March-April) and

among others it starts with the first-fruit eating ceremony of mango in the

month of Baisakh (April-May). All the rituals centering agricultural

operation, first-fruit eating, human, live-stock and crop welfare are observed

by the members of a village on a common date which is fixed by the village

head-man in consultation with the village priest.

Thus the ideological system of all the tribes surrounds supernaturalism. The

pantheon in most cases consists of the Sun God, the Mother Earth and a lower

hierarchy of Gods. Besides there are village tutelaries, nature spirits,

presiding deities and ancestor-spirits, who are also propitiated and offered

sacrifices. Gods and spirits are classified into benevolent and malevolent categories.

A peculiarity of the tribal mode of worship is the offering of blood of an

animal or a bird, because such propitiations and observance of rites are

explicitly directed towards happiness and security in this world, abundance

of crops, live-stock, plants and progenies. Sickness is not natural to a

tribal, it is considered as an out-come of the machination of some evil

spirits or indignation of ancestor spirits or gods. Sometimes, sickness is

also considered as the consequence of certain lapses on the part of an

individual or group. Therefore, riddance must be sought through propitiation

and observance of rituals.

Among all the tribes conformity to customs

and norms and social integration continue to be achieved through

their traditional political organizations. The tributary institutions of

social control, such as family, kinship and public opinion continue to

fulfill central social control functions. The relevance of tribal political

organization in the context of economic development and social change

continues to be there undiminished. Modern elites in tribal societies elicit

scant respect and have very little followings. And as the traditional leaders

continue to wield influence over their fellow tribesmen, it is worth-while to

take them into confidence in the context of economic development and social

change.

|

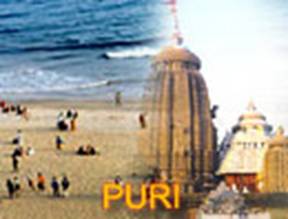

![]() Serene

Serene![]() Sublime ORISSA:

Sublime ORISSA:

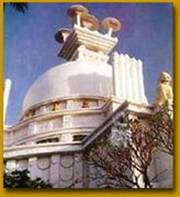

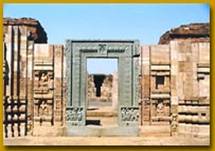

The earliest Buddhist Complex dating back to the 1st century

AD, Lalitgiri forms an important node of the Diamond Triangle ie Lalitgiri

(in present Cuttack district) and Ratnagiri and Udayagiri (in present Jajpur

district). Well connected by excellent roads to Cuttack and Bhubaneswar,

recent excavations here have brought to light significant archaeological

material that upholds Lalitgiri as a great centre of Buddhist attraction.

The earliest Buddhist Complex dating back to the 1st century

AD, Lalitgiri forms an important node of the Diamond Triangle ie Lalitgiri

(in present Cuttack district) and Ratnagiri and Udayagiri (in present Jajpur

district). Well connected by excellent roads to Cuttack and Bhubaneswar,

recent excavations here have brought to light significant archaeological

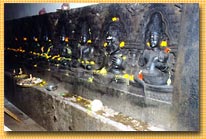

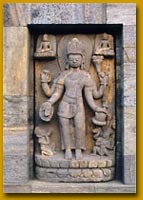

material that upholds Lalitgiri as a great centre of Buddhist attraction. In addition, the museum displays a large number of Mahayana

sculptures consisting of colossal Buddha figures, huge Boddhisattva statues,

statues of Tara, Jambhala and others. Interestingly, most of these sculptures

contain short inscriptions on them. The Standing Buddha figures, with knee

length draperies over the shoulders remind one of the influence of the

Gandhara and Mathura school of art. This also brings to mind the fact of

Prajna, who had come from Takshasila to ancient Orissa to learn the

philosophy of Yoga. He later left for China in the eigth century A.D.

with an autographed manuscript of the Buddhist text Gandavyuha, from the then

Orissan king Sivakara Deva 1, to the Chinese Emperor Te-tsong. The discovery

of caskets containing sacred relics, probably of the Tathagata himself, from

the stone stupa at the top of the hill, further enhances the sacredness of

the stupa as well as of Lalitgiri for Buddhists around the world. It also

brings to mind the description of Hiuen T'sang, the famed Chinese traveller

of the seventh century A D, about the magnificent stupa on top of a hill at

Puspagiri Mahavihara which emitted a brilliant light because of its

sacredness. " On the basis of archaeological materials including

inscriptions brought to light by excavation, Langudi hill in Jajpur district

may be identified as Puspagiri."

In addition, the museum displays a large number of Mahayana

sculptures consisting of colossal Buddha figures, huge Boddhisattva statues,

statues of Tara, Jambhala and others. Interestingly, most of these sculptures

contain short inscriptions on them. The Standing Buddha figures, with knee

length draperies over the shoulders remind one of the influence of the

Gandhara and Mathura school of art. This also brings to mind the fact of

Prajna, who had come from Takshasila to ancient Orissa to learn the

philosophy of Yoga. He later left for China in the eigth century A.D.

with an autographed manuscript of the Buddhist text Gandavyuha, from the then

Orissan king Sivakara Deva 1, to the Chinese Emperor Te-tsong. The discovery

of caskets containing sacred relics, probably of the Tathagata himself, from

the stone stupa at the top of the hill, further enhances the sacredness of

the stupa as well as of Lalitgiri for Buddhists around the world. It also

brings to mind the description of Hiuen T'sang, the famed Chinese traveller

of the seventh century A D, about the magnificent stupa on top of a hill at

Puspagiri Mahavihara which emitted a brilliant light because of its

sacredness. " On the basis of archaeological materials including

inscriptions brought to light by excavation, Langudi hill in Jajpur district

may be identified as Puspagiri." Ratnagiri in the Birupa river valley in the district of Jajpur,

is another famous Buddhist centre. The small hill near the village of the

same name has rich Buddhist antiquities. A large-scale excavation has

unearthed two large monasteries, a big stupa, Buddhist shrines, sculptures,

and a large number of votive stupas. This excavation revealed the

establishment of this Buddhist centre at least from the time of the

Gupta king Narasimha Gupta Baladitya (first half of the sixth century A.D.).

Buddhism had developed at this place - unhindered upto the 12th century A.D.

Ratnagiri in the Birupa river valley in the district of Jajpur,

is another famous Buddhist centre. The small hill near the village of the

same name has rich Buddhist antiquities. A large-scale excavation has

unearthed two large monasteries, a big stupa, Buddhist shrines, sculptures,

and a large number of votive stupas. This excavation revealed the

establishment of this Buddhist centre at least from the time of the

Gupta king Narasimha Gupta Baladitya (first half of the sixth century A.D.).

Buddhism had developed at this place - unhindered upto the 12th century A.D.  In the beginning, this was an important centre of Mahayana form of

Buddhism. During the 8th-9th century A.D., this became a great centre of

Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana art and philosophy. Pag Sam Jon Zang, a Tibetan

source, indicates that the institution at Ratnagiri played a significant role

in the emergence of Kalachakratantra during the 10th century A.D. This is

quite evident from the numerous votive stupas with reliefs of divinities of

the Vajrayana pantheon. Separate images of these divinities and inscribed

stone slabs, and moulded terracotta plaques with dharanis found in the

excavation at Ratnagiri.

In the beginning, this was an important centre of Mahayana form of

Buddhism. During the 8th-9th century A.D., this became a great centre of

Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana art and philosophy. Pag Sam Jon Zang, a Tibetan

source, indicates that the institution at Ratnagiri played a significant role

in the emergence of Kalachakratantra during the 10th century A.D. This is

quite evident from the numerous votive stupas with reliefs of divinities of

the Vajrayana pantheon. Separate images of these divinities and inscribed

stone slabs, and moulded terracotta plaques with dharanis found in the

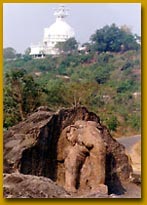

excavation at Ratnagiri.  The largest Buddhist Complex in Orissa, Udayagiri in the district of

Jajpur has assumed further importance after recent excavations which revealed

the ancient name of the monastery as Madhavapura Mahavihara. The excavations

also brought to light a sprawling complex of brick monastery with a number of

Buddhist sculptures. The entire area is found located at the foothills of a large

hill that acts as an imposing backdrop.

The largest Buddhist Complex in Orissa, Udayagiri in the district of

Jajpur has assumed further importance after recent excavations which revealed

the ancient name of the monastery as Madhavapura Mahavihara. The excavations

also brought to light a sprawling complex of brick monastery with a number of

Buddhist sculptures. The entire area is found located at the foothills of a large

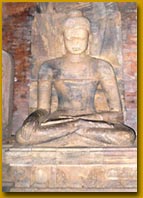

hill that acts as an imposing backdrop. The large number of exposed sculptures from the excavations, as well

as those still in situ, belong, obviously to the Buddhist pantheon and

consist of Boddhisattva figures and Dhyani Buddha figures. Interestingly,

although the site is located close to Ratnagiri (about 5 km), Udayagiri does

not possess a number of Vajrayana sculptures. Much is still to be known about

this site. In its present state, Udayagiri provides visitors a grand sight

with its newly excavated sprawling monastery complex that has to be reached

through a long stairway. The un-excavated area poses a mystery to

archaeologists, art lovers and lay visitors alike with the prospects of the

hidden treasures that lie buried. Adventure seekers will be thrilled by the

ascent to the hilltop. The hilly, serpentine, all-weather approach road on

the other side of Udayagiri is another added attraction.

The large number of exposed sculptures from the excavations, as well

as those still in situ, belong, obviously to the Buddhist pantheon and

consist of Boddhisattva figures and Dhyani Buddha figures. Interestingly,

although the site is located close to Ratnagiri (about 5 km), Udayagiri does

not possess a number of Vajrayana sculptures. Much is still to be known about

this site. In its present state, Udayagiri provides visitors a grand sight

with its newly excavated sprawling monastery complex that has to be reached

through a long stairway. The un-excavated area poses a mystery to

archaeologists, art lovers and lay visitors alike with the prospects of the

hidden treasures that lie buried. Adventure seekers will be thrilled by the

ascent to the hilltop. The hilly, serpentine, all-weather approach road on

the other side of Udayagiri is another added attraction. The study of Buddhist sculpture and art from the relics and

monuments in Orissa points to the gradual transformation of the Mahayana form

of Buddhism into the Vajrayana form of Buddhism by the middle of the ninth

century A.D. The large number of Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhist images and

figurines found in Orissa suggest that this form of Buddhism found a fertile

growing ground in Orissa. King Indrabhuti and his sister Lakshminkara of

Uddiyana were great exponents of this form of Buddhism. Uddiyan of ancient India has been identified with Orissa. The introduction of Tantric form of worship in the

Mahayana Buddhism ushered in a new stage in the development of the history of

Buddhism in Orissa, which attained its pinnacle of glory during the

Bhauma-Kara regime.

The study of Buddhist sculpture and art from the relics and

monuments in Orissa points to the gradual transformation of the Mahayana form

of Buddhism into the Vajrayana form of Buddhism by the middle of the ninth

century A.D. The large number of Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhist images and

figurines found in Orissa suggest that this form of Buddhism found a fertile

growing ground in Orissa. King Indrabhuti and his sister Lakshminkara of

Uddiyana were great exponents of this form of Buddhism. Uddiyan of ancient India has been identified with Orissa. The introduction of Tantric form of worship in the

Mahayana Buddhism ushered in a new stage in the development of the history of

Buddhism in Orissa, which attained its pinnacle of glory during the

Bhauma-Kara regime. From epigraphical sources it is known that Buddhism was popular

until the end of the Somavamsi rule in Orissa. From these sources, it is also

known that the Ratnagiri Mahavihara was a great centre of Buddhism. As if to

support this, we have a large number of Vajrayana sculptures at Ratnagiri.

These are different forms of Avalokiteswara, Manjusri, Heruka, Jambhala,

Kurukulla, Mahakala, Vajrasattva, Aparchana, Vajrapani, Tara, Aparajita,

Marichi, Arya Saraswati, Vajra Tara, etc.

From epigraphical sources it is known that Buddhism was popular

until the end of the Somavamsi rule in Orissa. From these sources, it is also

known that the Ratnagiri Mahavihara was a great centre of Buddhism. As if to

support this, we have a large number of Vajrayana sculptures at Ratnagiri.

These are different forms of Avalokiteswara, Manjusri, Heruka, Jambhala,

Kurukulla, Mahakala, Vajrasattva, Aparchana, Vajrapani, Tara, Aparajita,

Marichi, Arya Saraswati, Vajra Tara, etc. (3) In Orissa Mahali and Kol-Lohara practise crafts

like basketry and black-smithy respectively. The Loharas with their

traditional skill and primitive tools manufacture iron and wooden tools for

other neighbouring tribes and thereby eke out their existence. Similarly the

Mahalis earn their living by making baskets for other communities. Both the

tribes are now confronted with the problem of scarcity of raw

materials. And further they are not able to compete with others, especially

in the tribal markets where goods of other communities come for sale, because

of their primitive technology.

(3) In Orissa Mahali and Kol-Lohara practise crafts

like basketry and black-smithy respectively. The Loharas with their

traditional skill and primitive tools manufacture iron and wooden tools for

other neighbouring tribes and thereby eke out their existence. Similarly the

Mahalis earn their living by making baskets for other communities. Both the

tribes are now confronted with the problem of scarcity of raw

materials. And further they are not able to compete with others, especially

in the tribal markets where goods of other communities come for sale, because

of their primitive technology. (4) The tribes that practise hill and shifting

cultivation are many. In northern Orissa the Juang and Bhuyan, and in

southern Orissa the Kondh, Saora, Koya, Parenga, Didayi, Dharua and Bondo

practise shifting cultivation. They supplement their economy by foodgathering

and hunting as production in shifting cultivation is low. Shifting

cultivation is essentially a regulated sequence of procedure designed to open

up and bring under cultivation patches of forest lands, usually on hill

slopes.

(4) The tribes that practise hill and shifting

cultivation are many. In northern Orissa the Juang and Bhuyan, and in

southern Orissa the Kondh, Saora, Koya, Parenga, Didayi, Dharua and Bondo

practise shifting cultivation. They supplement their economy by foodgathering

and hunting as production in shifting cultivation is low. Shifting

cultivation is essentially a regulated sequence of procedure designed to open

up and bring under cultivation patches of forest lands, usually on hill

slopes. Shifting cultivation is not only an

economic pursuit of some tribal communities, but it accounts for their total

way of life. Their social structure, economy, political organization and

religion are all accountable to the practice of shifting cultivation.

Shifting cultivation is not only an

economic pursuit of some tribal communities, but it accounts for their total

way of life. Their social structure, economy, political organization and

religion are all accountable to the practice of shifting cultivation.